This is my first post to Substack. Having waited a long time to do so, it has three chapters and is a 12-minute read, according to Substack. This might strain most people’s attention span. Let me know!

Potential Disruption Due to Coastal Event

I ride my bike to the sea every morning. No matter how early I am out the door, the sun and humidity are oppressive. But the morning feels promising if my weather app warns of "Potential Disruption due to Coastal Event." It's a critical alert for fishermen, sailors, and other mariners, but for me, it signals that it might be an excellent morning for body surfing. Body surfing and the sea here in Yafo (Jaffa) deserve an extended narrative that will have to wait. Among other pleasures, it's a practice that ties me to my father, who taught me how to body surf in the Atlantic breakers on the Jersey shore, and to my son, who learned from me.

Biking along the sea on a wide promenade, I watch the board surfers, tiny black figures bobbing in the swells, and try to estimate how the surf will be for me. When I drop my few essentials on the beach and stare at the sea, other "potential disruptions due to coastal events" come to mind. At most, the beach at Yafo is 90 minutes by motor boat or car. A fast boat or car will get there much more quickly. Some mornings, helicopters streak across the sky, coming from the south, perhaps carrying wounded to hospitals. One morning last week, a crowd stood silhouetted on a bluff north of the beach where I swim. A helicopter was flying back and forth close to the water. A military or police watercraft was crisscrossing back and forth under the helicopter. A skidoo buzzed off the deck of the boat. I don't know what they were searching for.

Like everyone in Israel, I do things that might feel 'normal,' but there's another piece of me that is elsewhere. In my head, there's a list of risks to life, limb, and mind, especially now. Last Thursday morning, I was coming back from the sea at 7:30. The waves had been good. I had one superb ride but ended up body surfing the main road, wiped out when I turned right on a wet patch that had just been cleaned. I'm nursing scrapes and bruised ribs. A woman ran up when I hit the ground and helped me untangle myself from my bike. She was kind and asked whether I needed further help. She asked me if I knew the Hebrew word 'din,' which means judgment. She said, in essence, that there was something providential to the accident, and it could remind me to be more observant – and that life can change in an instant.

This past week, the Yafo waterfront was crowded with Israeli Arabs celebrating Eid al-Adha. Muslims comprise over one-third of Yafo's population. People laughed, greeting friends and family, attired elegantly, promenading along the sea. They lean against the railing with the sea as a backdrop and take selfies. They make barbecues on a grassy knoll or relax in the shade of pavilions on the beach side by side, with Jewish Israelis doing the same. Looking at these scenes, you wouldn't know there is a war on. You wouldn't know that a much graver, far more consequential war may begin any day now. Iran, its allies, and its proxies press on with their goal of extinguishing Jews and the Jewish state, no matter whose blood they shed and how much. Netanyahu, meanwhile, fiddles – a modern-day Nero, blaming others while the house burns down.

"Passenger Solomon, please identify yourself."

My most memorable experience flying to Israel was when I was 15 and traveling with older teenagers from Amsterdam. We were heading to Israel to work for the summer at Kibbutz Matsuva, far in the north – five kilometers from the border of Lebanon. Our El Al flight took off from Schipol Airport, but stopped in Munich to pick up more passengers. Leaving the Munich terminal, the plane taxied a distance, and the engines shut down. An announcement was made asking "Passenger Solomon" to identify himself. I was escorted to the door and peered out to see German security forces, automatic weapons at the ready. Stairs were wheeled up to the door. On the tarmac, the cargo hatch was opened. I was instructed to identify my suitcase. Emptied, the suitcase revealed a transistor radio. They told me to remove the leather case and open the battery compartment. The security forces abruptly relaxed. An official apologized to me. Passenger Solomon climbed back up the stairs to the plane. I got a lot of stares as I found my seat again. The engines started up, and we were aloft again.

The summer I worked on the banana plantations at Kibbutz Matsuva, the border was relatively quiet, but all the children slept underground. On October 18, 2023, Kibbutz Matsuva was evacuated when Hezbollah-led forces began launching thousands of rockets, missiles, and drones into northern Israel. About 120,000 people from the north of Israel were evacuated. Eight months later, they still are in temporary lodgings in other parts of the country.

Like all of Israel, Matsuva has to be understood in four dimensions. The ancient settlement, Pi Matsuva, is mentioned in the Talmud. The rabbis said that some western Galilee towns "were not considered part of the land of Israel, but whose Jewish inhabitants must still keep all the commandments prescribed for inhabitants of the holy land." Archaeologists uncovered ancient Matsuva in 2007 where they found Byzantine crosses on door lintels and pottery, indicating it was primarily a Christian settlement. In the 7th century, Persian invaders destroyed the town. Matsuva, like all of Israel, became part of the Ottoman Empire. With the downfall of the Ottomans after World War I, the British Mandatory government forbid Jewish immigrants to settle in the western Galilee. A determined group of a few hundred Jews from Czechoslovakia, Germany, and Hungary founded Kibbutz Matsuva in 1939. At that time, this region was overwhelmingly Arab. However, the United Nations partition of 1948 included the western Galilee in the slender region accorded to the Jewish state. Such are the quilts of claims throughout what used to be called the Middle East. Pointing to one or two historical events never tells the whole story.

Every centimeter of land is made of layers. Some layers are made from the sediment of ancient civilizations. The coastal city, Akko (Acre), dates back 7,000 years to the ancient Egyptians and Phoenicians. Israel and the entire region are built on sediment—geological and cultural. The older layers are hidden but periodically burst to the surface, accompanied by volatile gases that create social and political fissures. The land and the people we know are the product of titanic metamorphic pressures.

מצפה יריחו (Mitspe Yericho), 25 December 2022 copyright Paul R Solomon

"Why are you here?"

The trip to Kibbutz Matsuva wasn't my first time in Israel. And, since that summer, I have made several other trips, including a five-month stay from March to August of 2023, during a demanding period as the judicial overhaul deepened rifts between Israelis. On April 26, 2024, I returned to Israel after an eight-month absence and landed at Ben Gurion International Airport in Tel Aviv. On arrival, I was calm, if a little apprehensive, not knowing how Israel would feel with the war in its seventh month. In 'normal' times, planes from many countries land at Ben Gurion and disgorge thousands of people speaking Hebrew, English, Arabic, French, Russian, Amharic, and more. These streams of travelers would become a river flowing down a monumental two-part inclined slope. The ramp makes for an epic arrival. It brings to mind massive earthen ramps that Egyptians utilized to construct the pyramids. The ramp at Ben Gurion lets you know you've arrived in an ambitious country where technology and design are handmaidens.

Often, people who are making aliyah are among the arriving passengers. Aliyah signifies immigrating to Israel. Someone who makes aliyah is someone who ascends. Instead, the ramp brings every passenger closer to the earth—to the ground—to the adamah. (literally, red ground or earth)

Only El Al was flying from the US to Israel last April. The other airlines had canceled their flights. I landed at 11 a.m. The usual teeming crowds in the airport were gone. The massive intersecting ramps were different. Every meter was punctuated with photographs of the hostages held in Gaza by Hamas, who threw their victims onto trucks, draped over motorcycles, dead or alive. Family, friends, and strangers had left handwritten messages on the posters.

I didn't stop to look closely at the photographs that day. With Shabbat coming, I was in a hurry to get through immigration, pick up my checked baggage, and get to my cousins, about two hours north of Tel Aviv.

Ben Gurion International Airport, 26 April 2022. copyright Paul R Solomon

Only now have I looked at this picture I snapped. Since then, I've learned about many of the hostages pictured. Inbar Haiman, 27, whose image is at the start of the escalator and ramp, was a gifted artist and writer who studied at the University of Haifa's Academy of Design. Hamas abducted Inbar at the Nova music festival on October 7. Her family was notified of her death after being held captive by Hamas for 72 days.

22-year-old Alon Ohel, the bearded guy two steps from Inbar, may still be alive in Gaza. He’s known as a talented pianist with roots in Serbia. Hamas also kidnapped him from the music festival. After his capture, supporters painted his piano yellow, a color chosen to symbolize the hostages, and it was installed in Hostage Square in Tel Aviv.

The third poster shows a photo of Noa Argamani, 26, also abducted from the Nova festival by Hamas. One of the first videos Hamas published showed Noa Argamani screaming, "Don't kill me!" as a terrorist ripped her away from her boyfriend, Avinatan Or, and was taken to Gaza on a motorcycle by Hamas. Noa became the face of the Nova music festival hostages. She was one of four hostages rescued two weeks ago, on June 8, 2024. Avintan Or is presumed to still be in the hands of Hamas.

As I processed slowly along the shrine-like installation, I approached a Y-intersection as I had in past arrivals. To the left, a massive sign reads ISRAELI PASSPORTS. To the right, it reads FOREIGN PASSPORTS. Every other time I arrived in Tel Aviv, the crowd would split in two. The vast hall for those with foreign passports always entailed a long wait, the air thick with nervous, exhausted travelers. This time, I entered an empty hall. I was the only person with a foreign passport. A single uniformed immigration agent was waiting for me.

"Why are you here?" he asked. I gave him the name, address, and phone number of my cousin, who I would be staying with. The agent's next question took more work to answer. "When are you leaving?" I had arrived with a one-way ticket. I told him I'd be leaving at Chanukah to see family and friends in the US. This was not a good answer. He picked up the phone and gave my passport information to someone. Typically, tourists receive a three-month visa. I was dismayed when he told me I could only have a one-month visa without explanation. My efforts to change his mind were in vain. (Update: A week ago, my visa was extended.)

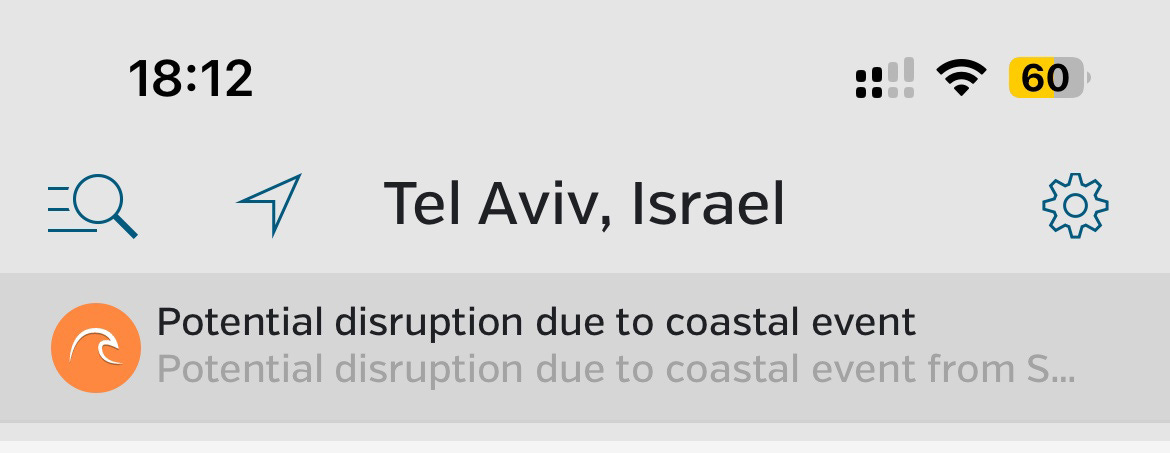

I was soon reunited with my two checked suitcases, and after a quick coffee in the arrivals area, I walked out into the sun. My rudimentary Hebrew was taxed as I negotiated a ride north. The drivers didn't know which roads to take to my destination, Hoshaya. Finally, I agreed to go with a driver who lives in Haifa, which was at least in the direction I needed to go. I opened Google Maps on my phone, wanting to look at the roads, and was momentarily shocked by what I saw.

Google told me this was my location – as did the Israeli apps, Waze and Moovit. After a minute, I remembered reading that the IDF had been jamming GPS locations for defensive purposes a while ago. During the week I spent in the north, location services remained blocked. I could navigate only by knowing a local address or specific location, such as a café, and then receive directions to my destination. It's akin to navigating using a sextant and sighting stars or the sun. It is especially disconcerting if you are in motion in a place you don't know.

So, why am I here?

Last August, on the night before I left Jerusalem, I told my friend Alana I'd return to Israel next summer. She asked me essentially the same question the immigration official asked me. I responded, saying that I had something to give to Israel, the birthplace of my father, my grandparents, and my other direct ancestors who returned to Israel from the Diaspora 213 years ago. What I could give to Israel was not clear. However, I am hopeful that my skills and passions across a broad interdisciplinary spectrum that fuels my teaching and creative work will be of value. More about this later.

Western Michigan University called me back to the US last August to teach in person. Weeks after my return, I was the target of allegations claiming that the content of my art courses constituted sexual harassment. Soon after, late in October, the administration put me on paid leave, booted me out of teaching, banned me from campus, and forbade me to communicate with students. It took the university three months to show me a document revealing that my punishment was based on a single student's claim that 'to the exclusion of teaching art, I was teaching about religion.' The previously hidden complaints made clear that I am a Jew and care about Israel. The university repeatedly violated our contract. I hired an attorney. Our union supported me. After six stressful months, I was able to negotiate a resolution that was favorable for me. The university signed a letter stating that four students made allegations but that no action was taken. I insisted on an agreement that allowed me to continue as a tenured full professor and teach online. The campus had become an unwelcome place.

Here, eight months into the war, I often feel dislocated, weighed down by the unknown, and grieved at what is known. My family in Israel and many friends here face excruciating, complex, existential decisions. All the Israelis I know have suffered lifetimes of loss. Layered over and under the realities here and now, is the detritus of what I experienced during the six months I was exiled from my university and forbidden to teach. I am not alone, as a resurgence of antisemitism has swept campuses. This hatred has not come out of the blue. I have more to say on this.